Why social impact must be accounted for like climate and nature

by Clodagh Connolly, Nicola Inge, Andres Schottlaender

View post

Anyone seeking to establish or maintain major infrastructure knows that social licence is difficult to earn and easily revoked. I approach this from the perspective of decarbonisation and the renewable energy transition, but it just as easily applies to highway construction, three waters infrastructure, or airport operation.

There’s no single accepted definition of social licence, but the Sustainable Business Council (SBC) in Aotearoa New Zealand has framed it as being: “An unwritten contract between companies and society for companies to acquire acceptance or approval of their business operations”[1].

SBC noted that this ‘unwritten contract’ requires confidence, trust, accountability, flexibility and transparency between the parties, and local communities are the ‘key arbiter’.

Why is this important? Because we find ourselves in a period of nation building – or rebuilding – with a desire to get things done fast, done well, and to benefit as many people as possible. Governments, industries, and communities should all be allies in achieving those desired outcomes. But the risk is that those parties will often be at odds. Building and maintaining social licence is a way of reducing and managing that risk.

Earlier this year, the proposed Fast Track legislation[2] touched a nerve in the broader public, leading to 27,000 submissions and a lengthy select committee process[3]. And in early October 2024, the government announced a list of the first projects that will be considered under the legislation once it is enacted. Of those 149 projects, 22 are for renewable energy developments. The proposed regime’s pro-development purpose would provide clear advantages to the energy sector, as with likely changes in 2025 to the RMA and National Direction. Supporting development can help deliver a successful energy transition, but despite the value in terms of national benefit, the legislative changes may be a double edge sword with regards to risk around social licence.

Does the proposed Fast Track legislation represent a risk to social licence for a company that seeks to make use of it? Greenpeace have said that “People are angry, and any company or organisation considering using the fast track would be wise to reconsider. Being associated with a project in the Fast Track, will mean they’ll be forever tarnished by that association.”[4]

Whether you agree or disagree with that statement, in my opinion doesn't matter. The point is that the concept of social licence is a live issue, and it won’t be going away any time soon. So, what’s the context for such oppositional and confrontational attitudes to have developed, and just as importantly, what does it mean for the success of the energy transition?

Social licence requires confidence and trust between the parties involved. And just like a relationship between individuals, trust between a company (or a government) and a community can take years to build, seconds to break, and forever to repair.

Research in Aotearoa New Zealand shows that trust in both businesses and government declined over the period 2022 – 2023[5], and the government of the day had almost entered into the ‘distrust’ zone. International research[6] suggests that trust in renewable energy businesses is in ‘neutral’ territory. However, at a human level, company CEOs rated poorly (as do government leaders and journalists). People have far greater trust in their peers and in scientists, more than in company technical experts. As demonstrated during the Covid pandemic, scientists who were also good communicators became highly trusted by the community at large – if not the committed anti-vaxxers. Siouxsie Wiles, Ashley Bloomfield, and Michael Baker come to mind.

In Australia, research undertaken by CSIRO looked at public attitudes towards wind, solar, battery, and transmission infrastructure development. It found that wind energy has broad public acceptance at a national level (65%), although 18% of people said they would outright reject a wind farm proposal. However, that 65% acceptance figure drops to 44% in rural communities, and 33% of those in rural communities would outright reject a wind farm proposal – almost double the national rejection rate[7].

Trust is also influenced by the nature of information consumption and exchange. Research has found that 46% of 18 to 24 year olds use social media as their primary news source[8]. Even Tik Tok has grown as a news source. The evolution of information consumption, and patterns of trust, have real implications for building social licence around energy or infrastructure projects. There is plenty of information about the energy transition, but it can be complex, hard to digest and inaccessible.

Seeking to build social licence isn't about achieving community consensus. It isn’t a singular process because communities are not homogenous, and development projects are dynamic.

Engagement can be seen as a process of change management[9]. Resistance to change remains a key barrier to establishing grid scale renewable energy projects, and to enabling good relationships with community stakeholders. Mauer’s three level Resistance to Change model doesn’t describe a linear process, but it does demonstrate an increasing resistance to change.

At Level 1 (“I Don’t Get It”), objections to change can be due to lack of information, or disagreement with data. Level 2 (“I Don’t Like It”), represents emotional resistance based on fear of loss. It’s typically deep-seated, not always based on rational thinking, and can hinder communication and decision making. “NIMBYism” is the term often used to describe this emotional resistance. Level 3 (“I Don’t Like You”) represents resistance toward an organisation or process, often due to mistrust or past negative experiences.

The strength of social licence can grow through traversing the journey from understanding, through acceptance, to a position of mutual trust. But it can be broken or retracted or diminished at any point, so ongoing and genuine engagement is essential.

There is an increased risk of ill feeling where an approvals process appears to favour the applicant and to limit engagement with the statutory process. It highlights the need for clear messaging, and transparent, responsive processes.

Examples of this include:

Social Licence to Operate can be thought of as a community’s measure of a project’s social performance, which SLR’s Social Performance team led by Esther Diffey - Technical Director, Social Performance is well placed to advise on. Social Performance refers to an organisation or project’s ability to avoid, mitigate and manage the adverse impacts they may impose on communities and enhance and optimise positive social outcomes through all phases of the project lifecycle from pre-planning to decommissioning and rehabilitation. Each project will have unique social and environmental dynamics, concerns, and opportunities. Customising action plans ensures that local needs and expectations are met effectively. Social Procurement is an example of Social Performance and is capable of being measured – both in terms of actions, outcomes, and money spent[10].

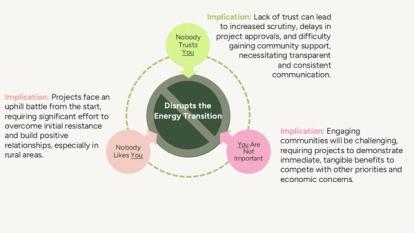

We live in an age of low trust in government; information gained through social media; and loss of social licence for corporates. Poor social licence has the potential to disrupt the energy transition, with potential outcomes being that:

Relatively low levels of trust in business, but especially in government, can add to the difficulty of building or maintaining social licence around energy and infrastructure projects. This is especially so in an evolving legislative environment that is seen as favouring the interests of business over those of the community and the environment.

In that context, at the very least being aware of social licence – and ideally, actively seeking to build it – is of critical importance for project developers.

Contact Mark for further information.

-------------------------------

References

[1] Source: Sustainable Business Council / Business NZ, Social Licence to Operate Paper 2013

[2] Fast-track Approvals Bill, Government Bill 31–1

[3] Recent changes signalled by the government seem designed to depoliticise some of the more controversial aspects of the Bill

[4] Greenpeace website - fast track consenting

[5] Source: Acumen Edelman Trust Barometer 2023: Trust in Aotearoa New Zealand

[6] Source: Edelman Trust Barometer: Australia Report 2024, Edelman. 2024

[7] Source: Attitudes Toward the Renewable Energy Transition, CSIRO. 2024

[8] Source: Communications and Media in Australia, Communications and Media Authority. 2023

[9] For example, Rick Mauer's ‘Resistance to Change’ model conceptualises how communities perceive and process change

[10] For example see Meridian Energy’s Integrated Annual Report which includes social and environmental reporting against UN and GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) standards.