Pillars for building community awareness and trust for a successful Battery Energy Storage System project

- Post Date

- 10 July 2024

- Read Time

- 10 minutes

The deployment of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) in Australia presents unique opportunities and challenges, particularly in the context of evolving regulatory frameworks, growing community expectations, and increasing emphasis on social responsibility. This article focusses on community and stakeholder engagement practice for BESS and the opportunities that present with the introduction of a new type of infrastructure. We will discuss this in the context of an evolving and dynamic regulatory environment and identify opportunities to get ahead of the game.

By equipping you with real-world insights and lessons learnt, we aim to empower all players involved in BESS projects to understand and effectively manage social risk, foster community acceptance, and drive positive outcomes for all stakeholders in Australia's rapidly evolving energy landscape.

The practical application: key learnings

Our team have prepared key factors to consider with your BESS project:

- Embed knowledge sharing, education, and community capacity building through information into project delivery.

- Assess and accept that the perceptions of community and stakeholders are real.

- Work collaboratively with communities to identify and mitigate social risks and define social performance 'success'.

- Tailor communications to audience level of understanding, with an emphasis on localised benefits.

- Manage expectations surrounding the key negotiable and non-negotiable elements of project delivery and opportunities for input.

- Demonstrate honesty, keeping commitments, and investing in relationships.

Key challenges

Some challenges facing productive engagement include:

Policy

- The machinery of Government turns slowly and, globally, there is broad discrepancy in policy thresholds and guidance for good engagement practice.

- Requirements and policies vary across levels of government and between states and territories.

Structural

- Private developments are profit-driven and the risk profile is required to reflect this.

- Project commitments are subject to regulatory and business decision-making which may change over the course of the project.

- The rise of cumulative impacts and fatigue associated with the mobilisation of a multitude of renewables projects in similar areas and regions.

Social

- Community uncertainty, mistrust and/or low levels of awareness can hinder the take-up of new technology.

- Growing community awareness and advocacy as a result of the rapid upswing in developments and new platforms for community opposition.

- Cost of living is a central concern and transition to renewables is seen as costly and may be met with opposition.

The Unexpected

Global events can interrupt and shift momentum, lead to resource constraints, or even halt projects as policy priorities shift or industrial frameworks adapt to new environments:

- Global financial crisis

- COVID-19

- Extreme climate events

- Political and industrial action

Resistance to change

Engagement is a process of change management. Resistance to change remains a key barrier to effectively embedding projects within the community and enabling productive and collaborative relationships with community stakeholders.

1. Rational objections due to lack of information, disagreement with data, or confusion

While there is an abundance of information available regarding Australia’s energy transition, that information is often complex, hard to digest and inaccessible.

In addressing resistance, we must cut through the jargon and priotitise simple, targeted and timely information. Particularly where new technology and/or sustainability concepts are introduced (BESS, circular economy), the onus is on us as the change-makers to first understand the capacity of the communities in which we work to interpret, understand and engage with new information. We are currently facing this level of resistance in relation to several BESS projects in Queensland. Awareness of this infrastructure is comparatively low and we find communities refer to their knowledge of associated projects such as solar farms. While both part of the same transition, the scale and impacts of these two types of infrastructure is vastly different.

2. Emotional resistance based on fear of loss

It is typically deep-seated, not always based on rationale thinking, and has the capacity to significantly hinder communication and decision making.

A risk-informed approach to engagement becomes absolutely critical here as we seek to understand the unique value and belief systems of the community and focus on building genuine, sustainable relationships.

3. Resistance toward an organisation or process, often due to mistrust or past negative experiences

Put simply, when people don’t like the outcome, they will attack the process. That is, even when people understand and support the proposed change (such as the transition to renewables), they may not like the location or the scale or the type of development proposed, or they just may not feel as though they have been afforded enough time to respond. Any and all of this can result in overall resistance.

Similarly, this resistance also speaks to what we are commonly seeing on the ground at the moment – an inability / failure of community to differentiate between projects and proponents and to instead view organisations collectively. It highlights the need for really clear messaging as well as processes that are transparent, responsive, accountable and comprehensively planned.

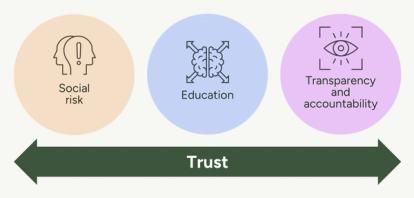

Social Performance critical pillars of success

In managing resistance to change, in turn alleviating barriers to social license and social performance, we see success in four key pillars.

These pillars underscore all of our strategic communications and engagement programs and are something we work closely with our clients to integrate within project delivery.

Social risk

A strong understanding of social risk

It must be recognised that unlike other forms of risk, social risk is population-specific; and is heavily informed by socio-economic factors and social values and perceptions. Consequently, social risk can evolve over the project lifecycle and as a direct result of shifts in perceptions, experiences and circumstances.

At SLR, we tend to adopt a risk-informed approach to engagement. This typically involves establishing a baseline understanding of community sentiment and social risk factors at the project’s outset. In doing so, we identify early some of the areas of potential harm and concern that will need to be addressed with project development, as well as the opportunities to leverage engagement processes to enhance social outcomes.

A simple example of where social risk has informed our process is demonstrated in recent projects across Western Australia. Our familiarity with project communities and the density of new wind farm development across the region meant that we recommended that engagement on new projects is scaled back. Where best practice typically guides direct engagement (door knocks and kitchen table conversations) with highly impacted stakeholders such as neighboring landowners, we recognised that these communities were fatigued and increasingly time-poor. Instead, we recommended scaling back to a more opt-in approach which trusted that landowners already possessed the knowledge and experience to make informed decisions about the level of impact and therefore involvement they chose to have in the project.

However, this approach is vastly at odds with our experience of a proposed BESS project in Queensland. In this instance, despite a lower level of approval and a smaller scale project, engagement needed to be ramped up in response to community concern about a new type of infrastructure and uncertainty about the impacts on a community which is, as yet, not as advanced in the transition to renewables.

Tailored messaging, reinforcing localised benefits, while taking a proactive and collaborative approach to mitigating risks assists in alleviating areas of resistance.

Education

Something that our Social Performance team is particularly passionate about, is the collective requirement for projects to embed education and knowledge sharing into their engagement programs to help communities navigate the complexities of the energy transition space.

Key considerations around education include:

- Information has potential to both empower and disempower

- There are varying levels of energy literacy

- Empowering communities as active participants, contributors, and enablers of Australia’s decarbonisation journey

- Embedding education and knowledge sharing to help communities navigate the complexities of the energy transition space and make informed decisions

Transparency and accountability

As we build community capacity through knowledge sharing and education, a key goal to anchor community discourse, is to establish a baseline acceptance of the fundamental drivers of the project as they respond to Australia’s energy transition goals, and the role that we each play as individuals in enabling that journey.

Where that understanding has been established, we often find that community and stakeholders value transparent project processes over project outcomes and personal preferences.

Transparency in process involves:

- Community understanding of the regulatory and approval pathways the project will follow

- Managing expectations surrounding negotiable and non-negotiable facets of project delivery

- Openly sharing information

- Discussing potential impacts and mitigation options collaboratively

- Consistently demonstrating how the project has heard, considered and integrated insights and feedback

Trust

The pursuit of trust underpins all other pillars of social success.

Relationships – and trust - are cultivated through consistently demonstrating a genuine desire to minimise adverse social consequences and enhance social outcomes (social risk), knowledge sharing (education), and process transparency and closing the loop (transparency and accountability).

How our Social Performance team can help?

Social performance refers to an organisation or project’s ability to avoid, mitigate and manage the adverse impacts they may impose on communities and enhance and optimise positive social outcomes through project delivery.

Social performance is both the process and the outcome, and it applies to ALL phases of the project lifecycle from pre-planning to decommission and rehabilitation.

We believe that the ‘newness’ of BESS and its rapid industry uptake presents a unique opportunity for a broad and coordinated public education program to build capacity of community and stakeholders to meaningfully engage with BESS proposals and provide a gateway to greater understanding of the electricity grid and the renewables sector overall.

SLR’s engagement practice employs a social research approach. We draw on the principles of Social Impact Assessment to conduct social risk and community sentiment analysis at the outset of our engagement planning. This process informs an engagement approach that meets regulatory requirements and expectations and is designed to suit the maturity of proponents and their communities. Rolled out over a program of BESS projects, it also provides a foundation for comparative assessment of changing sentiment and trust overtime and continual improvement as organisational, community and policy maturity increases.

Reach out to our team for further information, or to discuss how we can help on your energy transition project.

Recent posts

-

-

Unlocking value through solar PV repowering: A focus on module replacement and DC/AC optimisation

by David Fernandez

View post -