Understanding the European Commission's new Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA)

- Post Date

- 23 May 2024

- Read Time

- 11 minutes

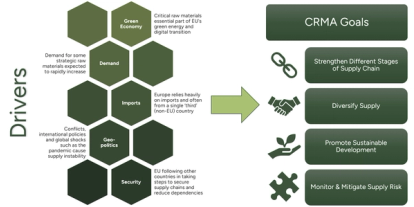

As part of the European Green Deal, the European Commission (EC) has agreed on new legislation referred to as the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) [1] to strengthen production, processing, and recycling of strategic raw materials in Europe and to diversify supply chains. It was agreed to in April 2024 by the European Council and European Parliament and will enter into force on the 23rd of May 2024.

It is big news for proponents of mineral exploration and mining, and for waste re-processing, refining and recycling projects containing critical raw materials across the globe. But time is of the essence for first movers. The deadline for the first round of applications for projects to be defined as 'strategic' (info below) opened in May and closes in August 2024,with the first projects defined in December 2024. The main drivers and resulting goals of the CRMA are highlighted below.

It has a bold mandate with lofty ambitions to reduce reliance on dominant suppliers of strategic raw materials and put the onus on EU member states to rapidly scale-up efforts to secure a stable, long-term supply of source materials for strategic purposes from within the EU and partner nations. The main targets of the CRMA for 2030 are below:

- >10% Mining - Mining in EU countries must account for >10% EU’s annual consumption of strategic raw materials (SRMs)

- >40% Processing - Processing of raw materials in EU countries must account for >40% of the EU’s annual consumption of SRMs

- >25% Recycling - Recycling in EU countries must produce >25% of the EU’s annual consumption of SRMs

- <65% Single-source -Single third-countries must account for no more than 65% of the supply of the EU’s annual consumption of an individual SRM

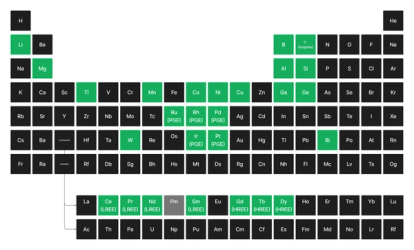

Strategic raw materials

According to the EU definition, Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) are materials of high importance for the EU economy for which there is a high risk of supply disruption. Strategic Raw Materials (SRMs) are a sub-set of the CRMs that have high strategic importance considering their use in advanced technologies (green and digital, defence and space applications). This includes battery materials such as lithium, manganese, graphite and nickel, technology materials such as rare earth elements and tungsten, and enabling materials such as aluminium and copper. A full list of SRMs is shown in the image below.

Strategic Projects

The main processes to achieve the targets of the CRMA are through streamlining development and permitting of ‘Strategic Projects’ (SPs) which incorporate development of national-scale exploration programmes, research and development on circularity of materials and recycling, promoting financing, monitoring and mitigating risks, promoting sustainable production, and promoting collaboration and partnerships.

SPs are projects that help to meet the goals of the CRMA and wider EU Green Deal and can be from a variety of sources not just mining. They should be flagship projects with respect to technological innovation and sustainability. Applications for SPs must contain a range of supporting evidence, including: detailed technical studies along with a timetable for development (including permitting), plans for social acceptance and engagement, and a business plan for assessors to understand the viability of the project. Strategic Projects are key to the CRMA, with some notable reasons below:

- SPs are focussed on strategic raw materials, but don't exclude other CRMs & can be by-products

- SPs will benefit from streamlined and predictable permitting procedures

- SPs should be a key tool for EU to accomplish CRMA objectives

- SPs should make meaningful contribution to the security of the Union’s SRM supply

- SPs would be flagship projects in terms of technological innovation and sustainability

- SPs would receive support gaining access to capital and offtake agreements

- SPs would aim to de-risk projects through EU support

- SPs are not restricted to EU nation states but other ‘third countries’

The main benefits to proponents having Strategic Project status within the EU are ease and speed of permitting, along with access to capital from potential investors through de-risking. For projects in ‘third countries’ (i.e. outside EU but considered strategic partners), the de-risking aspect still applies but also the EC has pledged to work with those partner countries to assist with permitting and sustainability practices, where possible. It is of particular note that projects can be classified as Strategic Projects even if the SRM is only a by-product of another commodity (such as rare earth elements from iron ore production).

United Nations Framework Classification (UNFC)

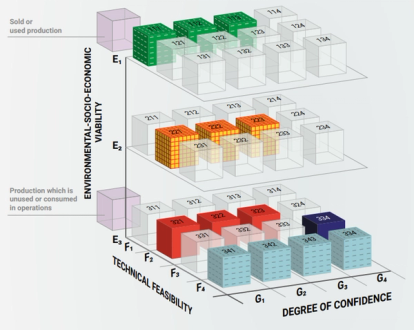

The United Nations Framework Classification (UNFC) framework is a tool designed for standardised classification and reporting – as well as ensuring sustainable development – of natural resources. It is another keystone of the CRMA as it allows all projects to be classified and reported – and therefore assessed – using the same criteria. UNFC-2019 [2] is the fourth version of the framework (after UNFC-1997, UNFC-2004, and UNFC-2009) and is used in collaboration with resource specifications, guidance documents, bridging documents, and country-level specifications.

It works on the basis of three axes of classification (shown in the image below):

- environmental-socio-economic viability (E)

- technical feasibility (F)

- degree of confidence (G)

Qualified Experts assess each raw material project with respect to each of these categories and report the quantities and qualities of material within each respective category.

Although not frequently used at a project level, the CRMA mandates project proponents to classify to UNFC. For those in the minerals and mining space, this is a similar process to classifying using mineral resource and reserve reporting codes such as those under the CRIRSCO umbrella. Updated guidance documents released in May 2024 [3] help companies to convert existing CRIRSCO-aligned reports to UNFC. A comparison of the main categories from CRIRSCO and UNFC is provided below.

![Table 1 – CRIRSCO – UNFC Comparison (Source: UNFC-CRIRSCO Bridging Document, 2024 [3])](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/b0ecix6u/production/ce1195ba36cf49b4427b2882c038132ad1757d60-1692x764.png?w=414)

Sustainability

Another key principle running through the CRMA is that of sustainability; projects being developed to achieve the goals of the CRMA must adhere to specific criteria with respect to sustainability challenges. This includes adhering to legal requirements and mandated guidance documents, committing to sustainability goals, reporting using sustainability schemes and declaring environmental footprints, as summarised below.

Legislation: first and foremost, critical material projects must be developed in accordance with EU and nation-state legislation. This includes minerals and mining, environmental and corporate governance legislation (including Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, CSRD).

Guidance: strategic projects must also follow guidance outlined in CRMA, including EU Principles for Sustainable Raw Materials, OECD due diligence, UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPBHR), UN Declaration for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), International Labour Organization (ILO) documents.

National measures: member states of the EU must also ensure sustainability practices are embedded and promoted across their raw materials supply chains. This includes promoting circularity and recovering materials from waste and recycling (with a particular focus on rare earth elements and permanent magnets)

Project proponent commitments: strategic projects proponents must commit to a number of sustainability targets and goals aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. These include: transparent business practices, respecting human rights, community engagement, renewable energy use (no fossil fuels), reducing waste and increasing circularity, water stewardship, and negative impact avoidance and mitigation.

Certification schemes: strategic projects must be part of a recognised third-party international sustainability certification schemes with multi-stakeholder governance. The EC is yet to define specific schemes; however, they will be assessed and themselves certified for use by the EC.

Environmental footprints: strategic projects will need to report their environmental footprints, through life cycle inventories / assessments. The EC will develop the reporting categories at a later date, but it will include greenhouse gas emissions.

Specific mitigation measures must be in place to protect air, soil and water along with biodiversity. Plans must be in place to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Concepts of circularity and waste minimisation must also be incorporated into project development. In order to ensure projects achieve social licence to operate they must protect human, indigenous peoples and labour rights, ensure continuous meaningful stakeholder engagement, and have specific plans in place to minimise negative impacts on local communities.

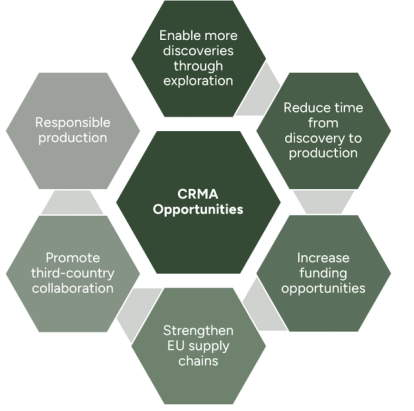

Opportunities and risks

Although widely hailed as an important step towards diversifying supply chains and ensuring security of supply for the EU, the CRMA is not a silver bullet, and there are many outstanding questions and criticisms. Some of the key opportunities, benefits, uncertainties, and concerns from various stakeholders are discussed below.

Key benefits:

- EU Member States – EU countries will improve security of supply and understanding of mineral deposit potential.

- EU-based projects – SRM projects in Europe will be fast-tracked to production and receive financial and off-taker support.

- Third-country projects – SRM projects in friendly jurisdictions (and considering single-country rules) should receive financial and off-taker support.

- Financiers – SRM projects will have considerable advantages over other projects with respect to development success.

- Environment – Localised supply chains and requirement for sustainable operations should reduce environmental footprint.

Key concerns:

- Community conflict – prioritising mining projects over other land uses may cause social unrest.

- Indigenous communities – possible human rights impacts (adhering to Free Prior and Informed Consent, FPIC, principles) e.g. where mining projects overlap with indigenous Sámi communities (and impacts on reindeer herding).

- Permitting speed – speeding up permitting may lead to reduced quality of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) as work is rushed, and could result in poor decision making.

- National capabilities – currently there is high variability amongst nation states relating to governance and the role of Geological Surveys and permitting authorities – this may impact exploration data acquisition and availability, permitting processes, and governance systems.

The CRMA has bold ambitions with tight deadlines. It will be a tough ask for each member state of the EU to develop and implement the required systems to enable the goals to be achieved. However, it does present opportunities for strategic mineral projects inside EU nation states to speed up permitting and (along with projects globally) to gain access to capital and offtake agreements.

Environmental and Human Rights groups have roundly opposed the CRMA due to environmental and social safeguarding concerns. Therefore, it is important projects are developed and operated with sustainability principles deeply embedded to ensure the industrial activity does not cause significant negative impact to the environment, local communities, and the wider population.

Get in touch with SLR experts to discuss your project needs from mineral exploration and mining, to waste, sustainability, and compliance challenges.

Related articles

-----------------------------------------

References:

- [1] Critical Raw Materials Act (2024): Regulation - EU - 2024/1252 - EN - EUR-Lex (europa.eu) - https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1252&qid=1715612182632

- [2] United Nations Framework Classification latest version (UN, 2019): UNFC-2019 - https://unece.org/DAM/energy/se/pdfs/UNFC/publ/UNFC_ES61_Update_2019.pdf

- [3] CRIRSCO Bridging document (CRIRSCO, 2024): CRIRSCO Bridging Document 2024 - https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/CRIRSCO_Template_UNFC_BD_ECE_ENERGY_GE.3_2024_5_ENG.pdf

Recent posts

-

-

Unlocking value through solar PV repowering: A focus on module replacement and DC/AC optimisation

by David Fernandez

View post -